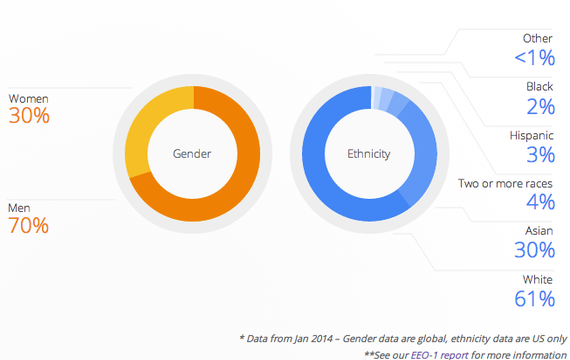

It has become a grand gesture in tech this summer for big companies to release demographic data about their workforces. It started back in May, when Google blogged about its lack of diversity, saying, “We’ve always been reluctant to publish numbers about the diversity of our workforce at Google. We now realize we were wrong, and that it’s time to be candid about the issues.” (In recent years, tech companies have fought to keep private the makeup of their workforces, calling such data a trade secret.) Google’s workforce, it said, is made up of 70 percent men and 30 percent women. Ninety-one percent of employees are white or Asian.  Google

Google

Google was widely praised for its effort. And rightly so: Some information is better than no information, isn’t it? The data helped to quantify a problem that has reached a boiling point in the industry. Google’s willingness to talk about that problem seemed to be, at least, a start. A litany of tech companies followed Google’s lead, using the formula it had established. And that formula has now become the de facto way to share (and apologize for) diversity data in Silicon Valley. It goes something like this:

1. Write a blog post about the importance of transparency, acknowledging how your company has a long way to go and outlining a few diversity-related initiatives

2. Include a sleek graph showing how few women and minorities you employ

3. When asked to talk about the issue, decline interview requests and redirect people back to the original blog post

On June 12, LinkedIn released its data:  LinkedIn On June 17, Yahoo:

LinkedIn On June 17, Yahoo:

Yahoo

YahooOn June 25, Facebook:

Facebook

Facebook

On July 23, after declining my request for demographic data earlier in the summer, Twitter joined the throng:

Twitter

Twitter

And on August 1, eBay, which similarly declined to provide data when I asked for it earlier this summer, made some of its workforce data public.  eBay

eBay

This drumbeat of diversity data has been anticlimactic, not least because it shows what most people already expected: that leaders in technology are overwhelmingly hiring white men. Often, when companies offered more granular detail, the gender divide was even more pronounced. Company-wide representation of women might be 30 percent, but the percentage of women in tech and engineering roles at Google and Yahoo, for instance, was about half that. All the companies say they need to do more. Few are willing to talk about the issue beyond what they’ve released in charts and blog posts. Plenty of people say, or whisper to themselves, that individual companies can’t fix the industry-wide “pipeline problem.”

The numbers—many companies hover around the 70 percent male, 30 percent female mark—and the method of communication have been strikingly similar from one company to the next. Conversations about diversity in tech have become as predictable as a campaign speech, a sad little “diversity parade,” as The New York Times put it. Beginning in May, I reached out to about two dozen leading tech companies to ask for demographic data and none of them agreed to be interviewed on-record about the issue (some offered prepared statements or answered questions through spokespeople via email). Many declined to share data (EA, Texas Instruments, Oracle), or didn’t respond at all to repeated requests (Amazon, Samsung, Cisco, Apple, Uber, IBM). Others rejected interview requests but provided numbers. As important as it is to get diversity numbers on the record, if what we’re interested in is changes to that record, it’s worth asking: Does releasing the numbers alone catalyze change? We have some evidence on this question. The answer is no. For example, HP has made its diversity data publicly available for more than a decade. In 2002, according to an annual report that year, just under 30 percent of HP’s worldwide employees were women.  HP

HP

A decade later, in 2012, women made up 32 percent of HP’s worldwide workforce, according to an annual report.  HP

HP

That same approximate 70-30 split persists at other companies that gave me demographic data about their employees. Salesforce reported 71 percent men and 29 percent women as of June 2014. Adobe, which has released diversity data since last year, has been at the 70-30 mark for the past five years, a spokeswoman said. (“Clearly these stats are nowhere near what we’d like to see and, even with an increased focus over the past few years, progress isn’t happening as fast as we’d like,” said Donna Morris, a senior vice president with Adobe, in a statement emailed by a spokeswoman.) SAP told me that 69 percent of its employees are male, 31 percent female. (The company declined to share data about race.) Oracle declined to provide data about gender or race, but its website says women make up 29 percent of the U.S. workforce. And, according to numbers I got from Intel, 24 percent of its employees are women and 76 percent are men.

Okay. So. We have all this data. We have acknowledgement from leaders in tech that we have a long way to go. We have a baseline of sorts. We also know that the numbers alone don’t foment change. Now what? Assuming the goal is to get to 50/50—workforce representation that reflects the gender makeup in the real world—how long could that take? And by what means? (Based on how long it has taken for the gender pay gap to shrink, it could take another half-century for women to get equal pay, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.)

What kind of commitment can we expect from tech companies to keep us posted about their progress? Demographic information about workers isn’t available for individual companies through public records. The Bureau of Labor and Statistics has industry-wide data broken down by gender and race, but it doesn’t have specifics from individual companies, agency spokesman David Kong told me. And it’s clear that women and most non-whites are underrepresented, but “whether there’s social discrimination or whatever, those are things I can’t talk about as a government employee,” he said. Within the tech industry itself, including among some women in leadership, there are those who say the issue is nearly resolved. Many companies have taken steps to add more women to their ranks, they say, and it will be only a matter of time before workforce censuses reflect those changes. “I do agree that there is a low percentage of women in technology and it’s definitely not where we want it to be, but I do think we need to be a bit careful not to overhype the issue,” said Pam Murphy, who is the COO of Infor and worked for more than a decade at Oracle before that. “I think the current generation of college graduates will look back at this and wonder why this got so much attention… There’s nothing which is prohibiting women coming into this industry. There’s no roadblocks.” If the industry cannot agree that there are obstacles to women entering the industry in the first place, it’s no wonder the scope of the conversation is limited. Even those who fixate on diversity in tech often focus too narrowly on gender. “We’ll talk about the fact that there’s sexism in tech, but we won’t talk about the fact that there’s racism,” said Tiffani Ashley Bell, CEO of scheduling app Pencil You In. “I feel like that’s the safe conversation. And mostly white women are highlighted, and mostly white women are talking about the issue—and they’re going to see it from that perspective.” Bell says that without a more open and inclusive conversation about diversity in tech, a few high-profile blog posts about workforce numbers isn’t going to make a difference. “You can be well intentioned, but if you don’t act on it—if you’re not actually doing anything—change is not going to come about just from you wanting to be inclusive,” Bell said. “It has to be something you’re actively doing. If you want to be more inclusive there are ways to do it.” Sharing data is part of the solution, but it has to be linked with meaningful initiatives to change corporate practices. Companies should release annual reports detailing their progress and publicly assessing the workforce diversification strategies that have and haven’t worked. That’s the next step.